Taking a look at the issues faced when trying to modify your source code and how Sourceror can help to solve them.

Introduction #

In 2019, Arjan Scherpenisse did a talk about the limitations of Elixir when it comes to programmatic manipulation of the source code. I highly recommend checking it out, as it gives some important context to this story. The most important issues are that the Elixir AST does not contain enough information to reconstruct the original source code, which makes this task almost impossible. Let's see why.

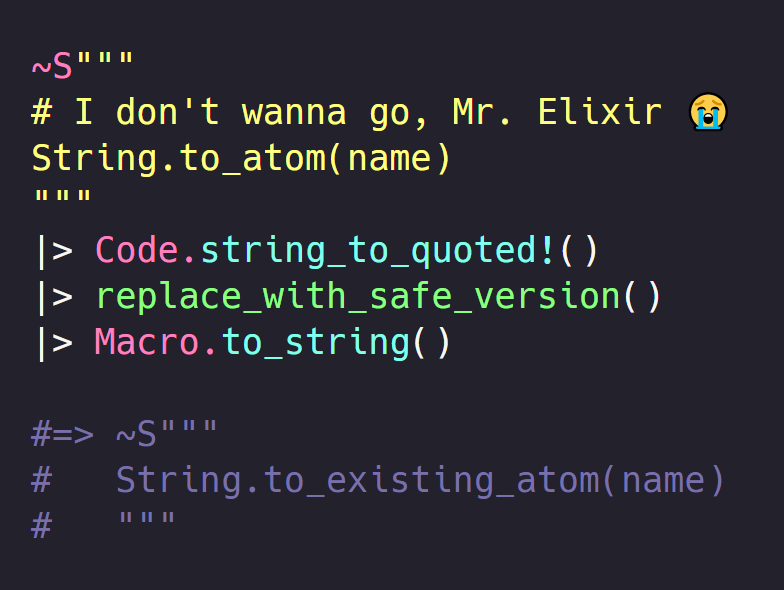

In the part 3 of the Elixir AST series we used Code.string_to_quoted to convert a string into its AST representation. We leveraged it to build a static code analyzer and point to issues or "code smells", but we didn't use it to actually fix those issues. If we look at this code:

String.to_atom(foo)A tool can recognize it's a call to an unsafe function, and recommend using String.to_existing_atom instead. To actually fix this, we need to transform the AST to use the safe version, and convert the AST back into a string:

code

|> Code.string_to_quoted!()

|> Macro.postwalk(fn

{{:., dot_meta, [{:__aliases__, module_meta, [:String]}, :to_atom]}, meta, args} ->

{{:., dot_meta, [{:__aliases__, module_meta, [:String]}, :to_existing_atom]}, meta, args}

quoted -> quoted

end)

|> Macro.to_string()This would produce the following code for the previous example:

String.to_existing_atom(foo)This seems to work fine, but what happens if we try with a slightly more complicated input like this one?

defmodule Test do

# some function

def foo(bar) do

String.to_atom(bar)

end

endRunning the previous transformation will produce something like this:

defmodule(Test) do

def(foo(bar)) do

String.to_existing_atom(bar)

end

endThe function name was replaced as we wanted, but the rest of the code is all messed up. There are two reasons for this. The first one is that Macro.to_string doesn't know about the context of the AST it prints, so it just wrapps all function call arguments with parenthesis. The second one is that the AST does not store the comments found in the code, meaning that they get lost in the string to quoted conversion, and we can't have them back when converting the AST back into a string.

This is the main reason why programmatic manipulation of the Elixir source code is troublesome.

There were some proposals in the past to incorporate comments into the Elixir AST to make this task easier, but they wouldn't be accepted for a couple reasons we will now address.

There are essentially two main approaches to this problem: to add a new kind of node to the AST, or to add more information to the existing ones. Adding a new node is the most complicated one; it introduces a breaking change in the Elixir language so big that it would break a lot of the existing macros, so this is not an option. Adding more information to existing nodes may be a more reasonable approach. Remember that most branch nodes and variables are 3-tuples, where the second element is the node metadata. It would be a good idea to store the comments there. For example, this code:

# Hello!

fooWould in theory be parsed to this node:

{:foo, [

line: 1,

comments: [

%{line: 1, text: "# Hello!"}

]

], nil}So far so good, but then how do we handle this case?

if allowed? do

foo

# Hello again!

endShould the comment be attached to the foo node? To the if node? Some heuristic needs to be used to determine to which node a comment should be attached, but nevertheless it's still doable.

The real issue is: how do we handle this?

# Just return ok

:okThe AST for :ok is... :ok. Literals like atoms, strings, numbers, lists and 2-tuples are represented by themselves in the AST, meaning they don't have metadata, and so we can't use this approach either. Proposing that the AST should be changed so that every node contains metadata is also troublesome for at least two reasons. The first one is that it's a breaking change, even more breaking than adding a new node, since there are a lot of macros out there matching on 2-tuples for keyword blocks like foo ... do ... end macros. The second one is that the Elixir AST is optimized for developer ergonomics, not for reconstruction. Some of the goals of Elixir are to boost developer ergonomics and productivity, and to be an easily extensible language through macros. If the AST were regular, that is if every node had the same shape, writing macros would suddenly become way more verbose and drastically impact the language. For example, a macro to support do blocks would go from this:

defmacro foo(do: block) do

# ...

endTo something like this:

defmacro foo({:"[]", _, [{{{:__atom__, :do}, _, _}, block}]}) do

# ...

endAnd you can imagine how more complex macros would explode in verbosity. This is a tradeoff made when designing the language, and considering how important macros are to the Elixir ecosystem, I think it's hard to argue it was the wrong choice, even if it means it's inconvenient for the use cases we'll cover in this article.

To summarize, the Elixir AST doesn't contain enough information to reconstruct the original source code, and we can't expect it to change to accomodate for this use case due to the massive impact such change would have in the language. The question now is: how can we work around this limitation?

Using an alternative AST #

If the AST used by Elixir is insufficient for our needs, then one answer to that issue would be to use an alternative AST. At first we may think that we need to build a custom parser so we can have our own custom AST, but there is a simpler solution.

When I first started investigating this topic and saw that Macro.to_string produced not-so-nice code, I recalled that Elixir ships with a code formatter that is able to produce nice code and in many cases also preserve the user choices, like the usage of underscores in numbers, sigil delimiters, and also the comments, which meant that the code was being parsed in such a way that the metadata didn't get discarded. Upon reading the source code for the formatter, my guess was correct.

One of the nice things about Elixir is that when the provided code doesn't fit your particular use cases, it usually provides some escape hatches to tune it for your needs, and the parser is no exception.

Parsing in Elixir is done in two steps: first the source code is processed by the :elixir_tokenizer, which converts the patterns it can identify into tokens, like a number, an identifier, a bracket, or the end keyword. These tokens contain line and column information, and in the case of literals they also hold the original string they matched. For example, a token for the do keyword would look like {:do, {1, 1, nil}}, and for the 0x10 integer it would look like {:int, {1, 1, 16}, '0x10'}. Notice how in the case of the integer literal the original representation 0x10 is preserved as well as the actual value 16.

The second step of the parsing is done by the :elixir_parser, created with Yecc, that receives the list of tokens generated by the tokenizer, and produces the AST we already know. The parser is smart enough to read the token metadata, and produce a metadata in the shape of a keyword list, labelling them as line, column, token for the original representation, and in some particular cases it may add more data useful to recognize the context where that literal was found.

These two steps are exposed to us via the Code.string_to_quoted function, and many of its options are forwarded to either the tokenizer or the parser. Luckily for us, the parser provides a hook that lets us change its behavior whenever it encounters a literal token, via the literal_encoder option.

The literal encoder is just a regular function that takes two arguments, the literal, that is 16 or "hello world", and the metadata. It must return a result tuple, with {:ok, ast} as the success value. If we pass a function like that as a literal encoder, then the literal nodes will be converted to whatever we return for such function. The Elixir formatter uses this to work around the limitations mentioned in the previous section, by simply wrapping the literals in a :__block__ call.

Such encoder is as simple as this function:

fn literal, metadata -> {:ok, {:__block__, metadata, [literal]}} endOr in its shorthand form:

&{:ok, {:__block__, &2, [&1]}}It is worth noting that by doing this we are changing the semantics of the code, and in many cases it would stop working. But for our use case we don't care about evaluating the code, we only care about having a way to manipulate the source code from its AST, so this is not an issue for us.

So, now we solved the issue of the AST not being regular and literals not having any metadata to store the comments in, but we still don't have access to the comments. The Elixir formatter has a solution for this, and this is where things start to get more fun.

The Elixir parser works with tokens, and at that stage the comments were already discarded, so we need to put our attention to the tokenizer. It is at this tokenizing step that comments get lost, but there is a way to retrieve them anyways. The tokenizer accepts an option called preserve_comments, but it's not as convenient as it sounds. It can receive a function of arity 5 that receives the comment information as well as the rest of the unparsed source code.

This function is not meant to change the tokenizer output and wont let you use an "accumulator" to store stuff. It forces you to use side effects if you want to take something out of it. We could use an agent, if the overhead of having to send potentially hundreds of messages all at once to the same agent is not an issue, or do what the Formatter does and temporarily store them in the process dictionary. Now, besides this inconvenience, the major issue of this option is that it is a private API, and we are not meant to use it. We'll now see a better way to get the same functionality.

The upcoming 1.13 Elixir version will introduce a Code.string_to_quoted_with_comments/2 function, that does exactly what the name suggests. It parses the code just like the regular Code.string_to_quoted/2 function does, but returns both the parsed AST and a list with the comments found in the source code, either as an {:ok, ast, comments} tuple or an {ast, comments} for the bang version.

Putting all of this together, we now get the primitives we need to start working on changing the code without losing data. Using that function with the literal_encoder option, we can get this:

iex> code = ~S"""

...> # Hello!

...> :ok

...> """

iex> options = [literal_encoder: &{:ok, {:__block__, &2, [&1]}}, columns: true, token_metadata: true, unescape: false]

iex> Code.string_to_quoted_with_comments!(code, options)

{

{:__block__, [line: 1, column: 1], [:ok]},

[%{text: "# Hello!", line: 1, column: 1, previous_eol_count: 1, next_eol_count: 1}]

}Awesome! We also used some additional options: columns and token_metadata give more information about the nodes, information like the column number, do and end positions, the sigil delimiter, and so on. The unescape: false prevents escaped sequences from being unescaped. For example, the text \n in a string would be unescaped into "\n", but since we are interested in the original representation, setting this option to false will preserve it as "\\n".

The next function we need to transform the source code is for a way to convert the AST back to a string. We saw that Macro.to_string was suboptimal because it doesn't respect the original formatting. The good news is that Elixir 1.13 also adds a new Code.quoted_to_algebra/2, that takes an AST and returns an algebra expression ready to be converted to a string/iolist with Inspect.Algebra.format/2. We can also use the :comments option to pass the list of comments we got from Code.string_to_quoted_with_comments/2, and now we have all we need to start working. Or do we?

Our goal was to have an AST that contains all the data, but what we have instead is an extended AST, and the comments as a separate data structure. This is great to feed them to the quoted_to_algebra function, but it's troublesome to navigate the AST and move stuff around. When we traverse the AST, the only way we have of knowing if there is a comment corresponding to the current node is by constantly checking the comments list, and even then it's hard to figure out correctly. How do we react to this?

:ok

# Some comment at the endOr this?

def foo() do

:ok

# More comments at the end

endTo finally have the AST with comments, we need to address this issue. Moreover, because we're relying on the Elixir formatter to produce the code, we need to do it in such a way that it still knows how to stitch AST and comments together. What the formatter does under the hood is to traverse the AST, check if there's a comment at the top of the comments list that can be associated with the current node, and print them. This means that if we change the AST or the comments in such a way that the line numbers get out of order, then the formatter will produce the wrong code. For example, if we change this code:

:a

# Comment!And we add more lines after the :a, but don't change the line number of the comment, then we end up with something like this:

:a

:b

# Comment!

:cSo there's actually two issues we need to address: merging AST and comments, and making sure the line numbers make sense to the formatter.

Enter the Sourceror #

What we covered so far is the process I followed when trying to answer the "how can I programatically modify the source code?" question. The two new functions I mentioned earlier are the result of a couple contributions I made to core Elixir so I could get started with the rest of the work. As a bonus, Macro.to_string now uses the new Code.quoted_to_algebra under the hood, so it produces the same prettified output as the formatter. Before doing this, I forked the Elixir code and started making some changes and prototypes to understand how all of this would work, and what heuristics would be needed to construct an AST with comments. The result of all this experimentation is Sourceror, a library that takes care of passing the correct options to the Elixir parser, and of merging and handling the AST and comments for you. All of the changes that were required in Elixir itself are also backported by Sourceror to Elixir versions down to 1.10, so you can try it out today!

The rules used to merge the AST and comments are quite simple:

- If a comment is placed before or in the same line as a node, then it's considered a "leading" comment.

- If a comment is inside of a block(like a

doblock, or the top level scope) and is not leading any other node, then it's considered a "trailing" comment.

With these rules, the code from the previous section would be parsed as the following tree:

iex> parsed = Sourceror.parse_string!(~S"""

...> # Hello!

...> :ok

...> # Some comment at the end

...> """)

{:__block__, [leading_comments: [], trailing_comments: [

%{line: 3, column: 1, text: "# Some comment at the end", ...}

]], [

{:__block__, [line: 2, column: 1, leading_comments: [

%{line: 2, column: 1, text: "# Hello!", ...}

]], [:ok]}

]}And to convert it back to a string:

iex> Sourceror.to_string(parsed)

~S"""

# Hello!

:ok

# Some comment at the end

"""The other nice thing about it is that it automatically corrects the line numbers of your code such that the formatter still produces the correct code. So if we add more lines, we don't need to manually correct the comment lines too:

iex> Sourceror.to_string({:__block__, [

...> trailing_comments: [%{line: 404, text: "Comment!", ...}]

...> ], [

...> {:__block__, [line: 56], [:a]},

...> {:__block__, [line: 705], [:b]},

...> {:__block__, [line: 23], [:c]},

...> ]})

~S"""

:a

:b

:c

# Comment!

"""So now we have all we need to transform the code, this time for real. So let's revisit the code we had at the start of the article. We have this code:

defmodule Test do

# some function

def foo(bar) do

String.to_atom(bar)

end

endAnd we want to replace the instance of String.to_atom with String.to_existing_atom, producing pretty printed code that preserves the comments. The only change we need to do to our previous function, is that it should now use Sourceror's parse and to_string functions instead of the builtin Elixir ones:

code

|> Sourceror.parse_string!()

|> Macro.postwalk(fn

{{:., dot_meta, [{:__aliases__, module_meta, [:String]}, :to_atom]}, meta, args} ->

{{:., dot_meta, [{:__aliases__, module_meta, [:String]}, :to_existing_atom]}, meta, args}

quoted -> quoted

end)

|> Sourceror.to_string()Which will produce the expected code:

defmodule Test do

# some function

def foo(bar) do

String.to_existing_atom(bar)

end

endOf course, if we wanted to target literals then we would need to match against something like {:__block__, _, [:ok]} instead of just :ok, meaning the AST is now more verbose, but that's as far as the differences go, and it's the tradeoff we're making to be able to reconstruct the source code.

Sourceror also provides other utilities, like being able to map a specific node to a range in the original source file, to perform changes to specific ranges of text, and an API to perform complicated and arbitrary navigations and transformations over the AST, and we will explore them in upcoming articles. In the meantime, you can check the Expanding the multi alias syntax livebook in the Sourceror repository.

Final words #

We've seen what are the complications when it comes to modify your source code in Elixir, what are the possible solutions, what has been tried and what's new in Elixir. We've also seen what is Sourceror, and how it solves these issue. The key takeaway here is that we no longer have the obstacles that were preventing the community to start building source manipulation tools.

Introducing an annotated AST and the necessary primitives to work with it lays the foundation for building advanced refactoring tools and IDE integrations, like the ones we would see in the Typescript or Java world. In ecosystems like JavaScript, people have adhered to a community standard AST representation of the code like the one used by Esprima, and on top of that tools like jscodeshift were built. I hope Sourceror to fill a similar role for the Elixir community.

While I was focusing on building Sourceror to be this foundation, folks like Andy Leak started working on a framework to build refactoring operations called Rfx. It's nicely coming together and it will soon be ready enough to be able to use Sourceror to perform complex refactoring operations and integrate with existing tooling like ElixirLS or Credo, so check it out too!

That's all I have for now. In follow up articles we'll discuss more about what you can do with Sourceror, and how you can adapt it to your own use cases, so stay tuned!